By Kristin Webster

This article was originally published in Volume 4 of Think Differently and Deeply, the publication of The Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School.

Every teacher knows how critical the opening days of school are, and in preparation for them, we run around setting up bulletin boards, building websites, composing lesson plans, mapping curricula, writing course expectations, and more often than not, waiting in long lines at the photocopier. It is the time of year when we think carefully about what we want to teach and how we want to teach it, and then take the steps to bring our vision to fruition. I believe that there are two other integral questions, however, that teachers often overlook but need to ask themselves as they head into the school year: how do I want my classroom to feel and what steps can I take to create this feeling in my learning space?

Students need to feel safe, seen, and valued in order for deep learning to take place. As Carissa Romero has argued, “students who are confident they belong and are valued by their teachers and peers are able to engage more fully in learning. They have fewer behavior problems, are more open to critical feedback, take greater advantage of learning opportunities, build important relationships, and generally have more positive attitudes about their classwork and teachers. In turn, they are more likely to persevere in the face of difficulty and do better in school.” (1)

It is our task then as teachers to take deliberate and thoughtful actions to build trust and a sense of community in our learning spaces. What transpires in our classrooms during the opening weeks of instruction—how we speak to our students, the opportunities we offer (or don’t offer) to them—conveys an unspoken and essential narrative. This is when our students develop their understanding of what happens in this space and determine how they want to behave within it. As Lisa Quay has eloquently summarized, “almost every situation is open to interpretation, and how people make sense of things determines their behavior.” (2)

Building a culture of trust and respect in the classroom begins with empathy, attention, understanding, and most importantly, a willingness to be flexible. Below are three tenets of this process; the list is by no means exhaustive, but will hopefully provide a helpful starting point for conscious and deliberate community building.

Focus on the Good and Create Spaces to Shine

As the CTTL has noted, “teachers should work to not only increase positive emotions in the classroom, but to also limit negative emotions” (3) by using positive, inclusive, and encouraging language. This does not mean that we should stop being critical. Identifying areas for growth, communicating these clearly, and determining strategies that enable students to tackle challenges head-on are all essential practices if we want our students to learn and progress. How we present this feedback to them, however, has a monumental impact on its efficacy, (4) and therefore teachers should strive to convey feedback in a way that “forestalls negative interpretations.” (5) (7)

By acknowledging and celebrating our students’ achievements, we show them they are seen and valued, which in turn fosters positive emotions and builds self-efficacy. We can do this through our verbal communications, written feedback, or providing a space in the classroom for students to showcase their own successes, such as an I’m Proud Of… bulletin board. The latter is a particularly powerful tool, since it promotes a broader, self-determined definition of triumph and offers a space for public recognition.

Read the Room and Be Flexible

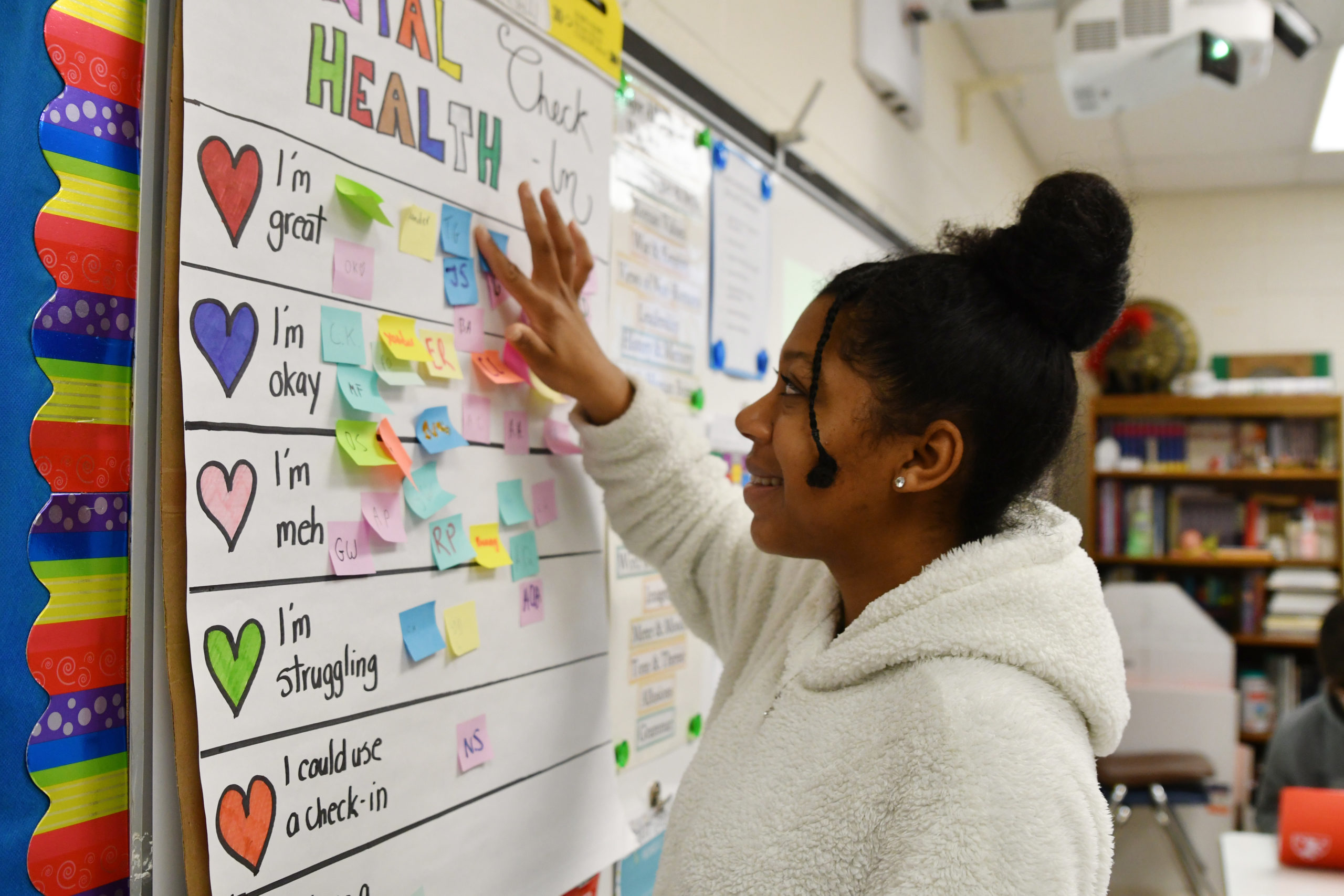

One of the simplest and most effective things we can do to foster empathy in the classroom is to provide our students with opportunities to communicate their feelings. Whether we ask them to circle their current emotional state on a Blob Tree, place a sticky note onto a Feelings Chart to communicate their mood (e.g. I’m great, I’m okay, I’m struggling), or do individual check-ins, we are conveying the crucial message that they are seen and cared for. It is also important to recognize that when students are in a heightened negative emotional state, it is hard for learning to happen. (6) As Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Antonio Damasio have made clear, “any competent teacher recognizes that emotion and feelings affect students’ performance and learning as does the state of the body, such as how well students have slept and eaten or whether they are feeling sick or well.” (7)

Taking five to ten minutes to acknowledge this and provide students with outlets to release anxiety or shift their headspace, rather than ploughing ahead with a lesson, not only validates them, but also results in more productive learning afterwards. By having a handful of stress-relief activities at the ready that are still connected to your content-area (in my case, this includes going outside to write out verb forms in sidewalk chalk or toss a beach ball to practice noun cases), you can help students refocus their energy and bring joy to the learning process.

Step Back and Let Them Lead

Giving students a voice in the classroom, whether it is designing a project, leading a review session, or rearranging the furniture, helps build a sense of inclusion and investment in their learning space. When we invite students to be active participants in our classrooms, to share their thoughts on the classroom culture and how this can be improved, we are communicating our belief in their abilities, showing our respect for their opinions, and creating a space where their needs can be vocalized and fulfilled.

By stepping back and allowing students to take the lead, we are also introduced to new vantage points—things we may have never seen or accounted for on our own. Asking students to create their own community norms or classroom expectations, for example, rather than dictating a list of rules to them, broadens the input, ensures more needs are being met, fosters a sense of inclusion, and promotes student interest in upholding these guidelines, since they were the authors of them.

Building a classroom environment of trust and respect, where students feel safe, seen, and valued, requires thoughtful and conscious planning, open communication, and the willingness to take risks and remain flexible. The effort invested in this process, however, has immediate and long-lasting results: a learning space where students can flourish and deep learning can take place.

Kristin Webster (kwebster@saes.org) teaches Middle and Upper School Latin at St. Andrew’s.

Learn more about the relationship between emotion and cognition by enrolling in the Neuroteach Global Student Success & Well-being track, a series of micro-courses focused on research-backed study strategies for students of all ages and abilities, the mindsets and metacognition of successful students, and student well-being via brain need management

Footnotes

1 Carissa Romero. What We Know About Belonging from Scientific Research. Mindset Scholars Network. 2015, 1.

2 Lisa Quay. The Science of “Wise Interventions”: Applying a Social Psychological Perspective to Address Problems and Help People Flourish. Mindset Scholars Network. 2018, 1.

3 The Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning. Classroom Culture: Field Guide. Neuroteach Global. 2019.

4 Carissa Romero. What We Know About Belonging from Scientific Research. Mindset Scholars Network. 2015, 4.

5 Lisa Quay. The Science of “Wise Interventions”: Applying a Social Psychological Perspective to Address Problems and Help People Flourish. Mindset Scholars Network. 2018, 3.

6 The Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning. Classroom Culture: Field Guide. Neuroteach Global. 2019.

7 Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3–10.