By Dr. Ian Kelleher (1)

Note: This article was written before school campuses closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We invite you to apply Dr. Kelleher’s recommendations to your remote, hybrid, or in-person teaching.

At St. Andrew’s, we are living through year two of our new daily schedule (see “Think Differently & Deeply Volume 3”), designed to deepen learning and support student well-being. It is based on the fundamental principle that deep academic challenge and well-being are intertwined — that great schools design for both, rather than force students and parents to make a false choice. The flow of each day and the school week as a whole has been a revelation. But this got me thinking: changing a schedule is a large scale effort. What was I doing on a smaller scale in my physics class to combine rigor and well-being, strategies that could be done by any teacher without asking permission? Here are just a few:

Disrupting the rhythm

When I started teaching I fell into a familiar rhythm, like the beat of a dance track: quiz, quiz, quiz, test, quiz, quiz, quiz, test… Everything counted. But a light went off while in a conversation with a colleague who said, “Sean is so good on tests; it is a shame his quiz grades are so low, they are really dragging his grade down.” It was a revelation — surely his test grade was by far the most important measure of what Sean ultimately knew, and if he failed the quizzes but ultimately learned from them, why should the quizzes count against him?

Formative Assessments

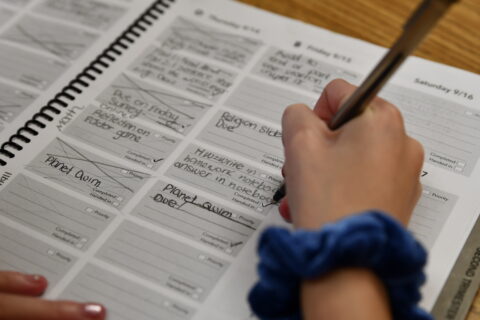

And then I learned about formative assessments. One of the most dramatic changes since I have started using research to inform my teaching has been knowledge and impact of formative assessments. They are a low- or no-stakes tool to find out what students currently know and can do, and what they are still struggling with. And then, importantly, I can alter my teaching based on what I find out, and get students to alter their practicing and studying based on what they find out. I made the commitment to never put a concept, skill or block of key knowledge on a test that students had not previously encountered on a formative assessment. This commitment made me change the way I design my day-to-day teaching to make it happen. I also talk to my students about what formative assessment is, why we are doing it, and how we are shifting things about a bit in my course based on what we find out. On occasion I move a test when it is clear my students are not ready. I used to think that if I felt I had done an awesome job teaching, my students must be ready for that test. I now realize that just because I may have walked out of my classroom feeling that, wow, my teaching was awesome today, it doesn’t mean the learning I wanted to happen had actually happened. Formative assessment is the way to find out. (2) Including regular formative assessment and a regular dialogue about it with my class has lessened the stress level around major assessments as students know where they are and have an opportunity to act while there is still time. Without quizzes I have fewer grades in my grade book, so in essence each test counts for more, but the stress level is down because students feel better prepared for the test. There appears to be no negative impact on grades, and it seems to actually help some students.

Teach strategies alongside content

I used to believe that my job was to teach content. By the time students reached me they had a good toolbox of skills, now it was up to me to deliver chemistry and physics. I now know from research that most students, left to their own devices, use ineffective or inefficient study strategies, like rereading the textbook with lots of highlighters. I also know that students’ ability to carry over skills that work in one class to another, or from one year to another, tends to be much less than we appreciate, and they benefit from an intentional academic nudge to use their prior knowledge and skills on current tasks. (3) So now I teach study strategies alongside content, particularly active retrieval and spaced practice. (4) Active retrieval is the idea that self-testing is much more effective for long-term memory storage and retrieval than passively reading. Spacing is the idea of allowing students some time to get a bit rusty before making them recall information or skills that they are just starting to forget. I design the content and schedule of my homework with active retrieval and spaced practice in mind. The goal of most of my homework is to get students ready for assessments through a planned sequence of just-forgetting, forcing yourself to recall, then checking in with your notes or with me when you cannot. This is another part of helping reduce students’ stress level for assessments by making them feel better prepared, and by increasing their confidence that they have a great toolbox of strategies to draw on.

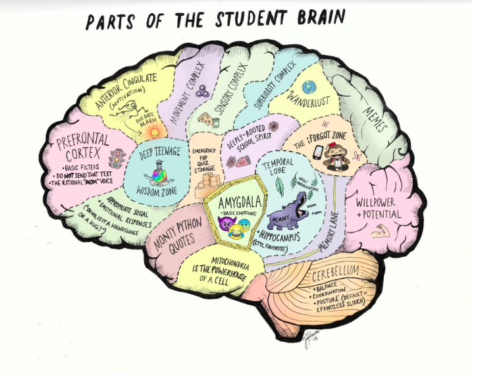

Acknowledge limited working memory

I used to think that being able to hold 20 things in your brain at once was part of learning science. Some people could do it, others could not; this was just part of the process of figuring out if science was for you. I now appreciate that working memory and higher order thinking are separate things. Related, yes, but particularly in the novice stage of learning the core knowledge and skills in a new subject, working memory capacity can be a real barrier. (5) You are asked to hold so many things in your working memory at once that you do not have the capacity to do the task. Or you can do the task now, but do not have the capacity to commit it to long-term memory so you can do it later. So now I build knowledge step-by-purposeful-step, lessening the demands on students’ active working memory because key skills and knowledge for the learning now had already been stored in long-term memory earlier. It feels easier to students because of this. I also add in simple scaffolds to reduce the cognitive load at times, such as providing worked examples for homework in the early stages of learning a new skill, or allowing students to use a sheet of equations when we start a new unit. These scaffolds will get peeled away over time as students’ confidence and competence grow, but they lessen stress when students are in the ‘novice’ stage of a new topic.

There is, of course, much more, and it evolves constantly. Once the idea is fixed in your mind that well-being and academic challenge go hand in hand, it becomes a part of your daily lesson planning. Some degree of stress helps learning, but lots does not — so as a teacher I am constantly a stress balancer. We might think of this as a two-pronged approach to well-being that includes strategies for instruction and assessment, and social-emotional strategies, some of which are shown in the table below. By designing for the well-being of my students I am also building my capacity to get them to think harder and dig deeper. Yes, as a school we can do that through large-scale projects like a daily schedule. But as a teacher, I can do it every day too.

Dr. Ian Kelleher (@ijkelleher) teaches Science at St. Andrew’s where he is the Dreyfuss Family Chair for Research and co-author of “Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education.”

A two-pronged approach to well-being (includes, but is not limited to…)

Instruction & Assessment

- Teach memory strategies alongside content

- Be deliberate about metacognition

- Teach and assess in multiple modalities

- Use formative assessment

- Use research on what good feedback looks like

- Curriculum design (interleaving & cognitive load)

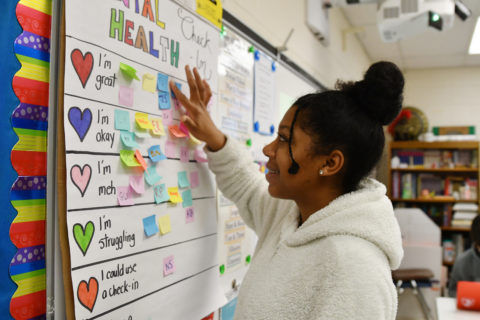

Social-Emotional

- Belonging mindset & identity formation

- Growth mindset

- Purpose and relevance

- Metacognition about stress

- The language a teacher uses

- The importance of relationships

Footnotes

1 The title was created by Stanford University’s Denise Pope for a workshop that Denise and Ian co-presented at SXSW EDU2019.

2 Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.

3 Quigley, A., Muijs, D. & Stringer, E. (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning, Guidance Report. Education Endowment Foundation.

4 Pashler, H., Bain, P. M., Bottge, B. A., Graesser, A. C., Koedinger, K. R., McDaniel, M. A., & Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning, IES Practice Guide. National Center for Education Research.

5 van Merrienboer, J. J. G., Kirschner, P. A., & Kester, L. (2003). Taking the Load Off a Learner’s Mind: Instructional Design for Complex Learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 5–13.