I distinctly remember in 1997 during my interview for a position teaching history and coaching soccer at St. Andrew’s (Maryland), then Head of the Upper School John Holden saying, “we expect you to be a better educator each June than you were the previous September.” I liked the challenge, I liked the people who would be pushing me and supporting me with that challenge, so I took the job.

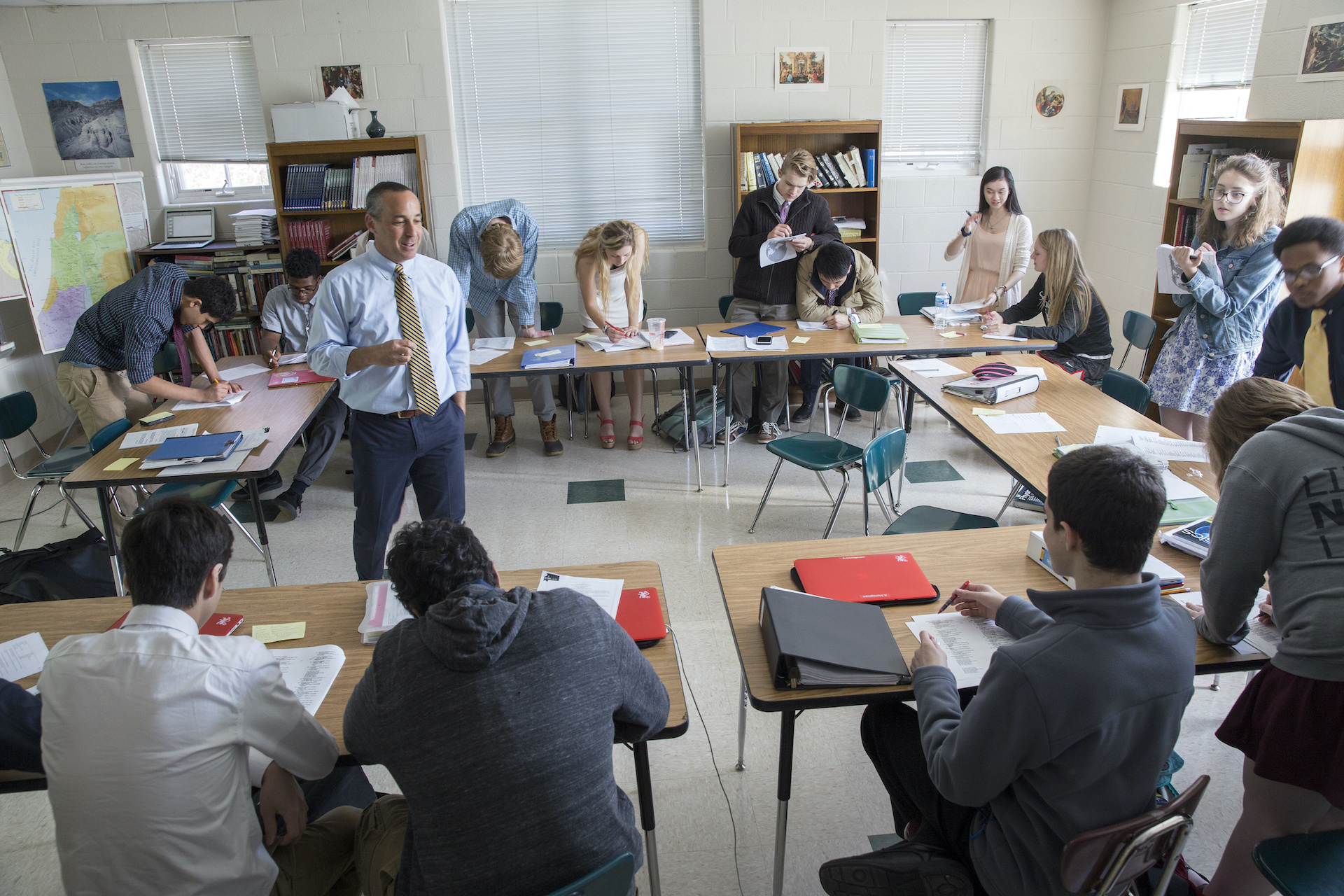

Likewise, as a history teacher at St. Andrew’s, I expect my students to be better historians each June than they were when we first met in September. Because of what I know about neuroplasticity – that our brains are always changing as a result of the experiences we have – I have always thought this to be possible for every student. Not every student will grow in the same way and every student will grow different amounts in different areas. One of the joys and privileges of being a teacher is watching the story unfold and helping each student on this journey. But one challenge we face as educators is how to measure such growth.

The Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning has an amazing team of teacher-researchers, and we have been fortunate to have been coached by university researchers who help us think about qualitative and quantitative research methods in a complex school setting with many variables. After years of listening to friends such as Dr. Beth Morling, Dr. David Daniel, Dr. Kristin Gagnier, and Dr. Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, I am determined to get a better baseline of where my students are when they start my class in September. This will allow me to compare where they end my class in June. Too often, I have missed the window of opportunity that exists during the first few days or weeks of school before diving into the content-rich curriculum that looks, as the course is titled, at the United History in a Global Perspective.

This fall, along with my history teaching colleagues, we are asking students to answer questions around the essential content and skills of the class. We will do this at the very start of the year, interleave the same questions some more at intervals over the course of the year, and ultimately use them as part of how students are summatively assessed on their final exam in early June. The content and skills we base our questions on are tied to ten learning progressions we have developed and are piloting for the course this year with guidance from Learner-Centered Design.

As you launch into another important school year for each of your students, think about ways to measure their growth in a more objective way by establishing an early baseline. This might well be a “no stakes” formative assessment. It could include a collection of initial evidence of a student’s reading, writing, problem solving, creative ability, or any of the many other important ideas of skills in your class – the things we really hope stick in our students’ brains during their year with us. This initial baseline can then be compared to a follow-up assessment at the end of the year, or to check-in assessments at convenient points during the year too. You can make it part of a portfolio process, though you don’t have to. You can find ways to include each students’ voice in the process too – what do they make of their progress? What are their thoughts and what happens next? How do they think you can best support their growth? If the window of the start of the school year seems too daunting to meet, consider when in the first six weeks it makes sense to do so. Or where else in the year can you establish a baseline to measure growth on an essential topic or skill that you are about to work on?

As veterans of our summer Science of Teaching and School Leadership Academy know, we try to present manageable ways for teachers to collect evidence from their students. Time is always the prize for teachers, so it is good to point out that whether they realize it or not, teachers are always collecting observational data on their students in a thousand unnamed ways each day. Even if you decide you are unable to fit in the formal baseline data collection, you are still generating evidence every day. But what do we do with it? We simply suggest that you be a bit more deliberate and purposeful.

Based on this evidence, we hope teachers are thinking about how to tweak or even rewrite their lessons, assignments, and homework to better reflect where students are and what they need next. We hope they are thinking about what new pedagogical strategies might work well, or how the current pedagogical strategies should be tweaked. We hope they are thinking about what learning strategies they could be sharing with their students to help them improve their outcomes. This deliberate, thoughtful use of the myriad daily evidence we collect to inform what we do next is in the spirit of what David Daniel has called “evidence generating teaching.” It is verging on what others might call action research, but is noticeably different as at its core are short, tight recursive loops where we try something out, collect evidence of how it went, plan what to do next based on this evidence, and repeat, and repeat some more.

What should you try out? Use your CTTL Roadmap or Placemat, Neuroteach, Neuroteach Global, or check out our Research Base for ideas from MBE. Then combine this with your own professional wisdom, the collective professional wisdom of your colleagues, and your own secret sauce as a teacher. In this fashion, you are translating MBE principles in everyday actions for your context. Try one out, see how it goes, plan what to do next based on this evidence, and repeat.

Whereas action research might happen once every few years, evidence generating teaching should be happening many times every year. Even when we are not deliberately doing an evidence-generating teaching cycle we should be evidence-generating teaching in how we go about our days. So even if you cannot find the time to plan a baseline collection with your students, please commit to being an evidence-generating teacher at least once this year.

As I conclude this piece, I find myself returning to John Holden again. He would open each new school year with a “fresh start” speech. Our students are coming to us fresh and different after time off during the summer. Let’s find out where they are, and measure how far they will go during this school year through the deliberate use of pre- and post-measurements. And let’s aim to be the best evidence generating teachers we can be to help support that growth.