By Glenn Whitman

My first introduction to neuroanatomy was in 1983 as a 9th grade biology student at Mt. Pleasant Junior High School in Livingston, New Jersey. I earned a B in the class, which can be verified by my archived report card that my mother saved along with other documents of my childhood. Though I did well in the class, I don’t remember anything except dissecting a pig. I could never have guessed that biology would play an important role later on in my future as a history teacher.

I began my first teaching job after graduating Dickinson College in 1991. With a degree in history, I headed northwest to Spokane, Washington to teach AP United States history and middle school history as well as coach boys’ soccer. My first-year teacher instincts were to make sure I knew my content, and thankfully I was able to refer back to notes I had retained from my own AP class experience as well as the history courses I took in college. In all transparency, I thought little to nothing about each student’s brain. My thinking was I teach, and they learn.

Things have certainly changed for my colleagues and me at St. Andrew’s as we now enter our 11th year in the school’s journey in using Mind, Brain, and Education Science research to inform, validate, and transform how we design school, classes, and work with each individual student. Our school’s journey, which led to the creation of the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning in 2011, has led us to serve as a model for other schools working to translate the MBE Science of Learning into their school contexts with their students.

There has been a great deal of questioning about how much neuroscience can help teachers teach and all students learn better. When the CTTL gets the chance to conduct workshops for public, charter, and private school teachers around the world, we often commence by introducing the trans-disciplinary MBE field that is at the intersection of neuroscience, behavioral psychology, and education theory. However, we often downplay the role neuroscience can play in what a teacher does, which drives our decision to call the work we are doing MBE, rather than solely neuroscience.

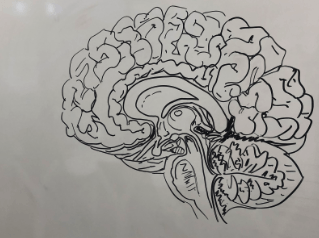

I have decided to write this month’s issue of the CTTL’s “Bridge” to begin elevating neuroscience, in particular to highlight the need for teachers and students to know “just enough” about it to inform each of their thinking about learning. I was also partially inspired by this sketch that greeted me on the CTTL’s whiteboard one afternoon as the CTTL’s Head of Research, Dr. Ian Kelleher, was doing some recording for one of the Neuroteach Global micro-courses that he was designing. The powerful statement that was written above it, “We are the first generation to understand how the brain works. But how has teaching changed as a result?” propelled me to write this “Bridge.”

What if teachers knew more about the limbic system that includes the amygdala and hippocampus? What if teachers knew more about the prefrontal cortex, corpus callosum, a neuron, axon, synapse, myelination, synaptic pruning, and, most importantly, neuroplasticity? Try for a moment this short matching formative assessment that is from the CTTL’s Science of Teaching and School Leadership Academy workbook, and see what you currently know (answers at the end of this “Bridge”):

Word bank:

(A) neuron

(B) corpus callosum

(C) myelin

(D) synapse

(E) axon

(F) the limbic system

(G) neural impulse

(H) hippocampus

Match the brain part to the correct description

__ i.) Thick bundle of fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

__ ii.) A brain cell

__ iii.) The long, thin projection of a brain cell that electrical impulses travel along

__ iv.) The white fatty sheath around (iii)

__ v.) The tiny gap between one neuron and another

__ vi.) The electrical signal that travels between one neuron and another

__ vii.) The emotion system of the brain, which includes the amygdala

__ viii.) A part of the brain very involved in memory, as well as emotion and other functions

For me, holding such knowledge of neuroscience and neuroanatomy has helped me:

-

Dispel neuromyths such as “I am a left-brain learner, or I am a right-brain learner” because we know from fMRI scans of the corpus callosum, the cross hemisphere “super highway,” that both sides of the brain light up when learning (though not equally).

-

Learn about myelination and elevated my use of memory strategies, including the spacing effect and interleaving, both of which I have been exposed to through the work of Efrat Furst, Mark McDaniel (co-author of Make It Stick), and Pooja Agarwal (co-author of the forthcoming book, Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning).

-

Think about the effect that stress, emotions, and sleep (or lack thereof) have on the limbic system and one’s learning. Dr. Judy Willis, who might have the best url among anyone I know, www.RADteach.com, first introduced me to this knowledge.

-

Deepen my understanding of the executive functions that are central to the prefrontal cortex, which has allowed me to talk about executive functions more effectively. Here is why: early on in the work of our school and the CTTL in theMBE field, whenever someone would talk about executive functions, it would come with the label of “disorder.” However, by learning that every individual needs executive functions, to, dare I say “function,” we have been able to demystify this label because of how we can connect it to a brain’s anatomy.

-

Increase my use of dual coding when I lecture or ask students to transfer knowledge from narrative to visual (or vice versa) after considering how the brain receives, filters, stores, and accesses experience and information.

Elevating the discussion of how neuroscience and neuroanatomy can help teachers and school leaders think about learning has led us to incorporate a neuron building activity into all of our workshops. If you want to take it one step further, try ordering sheep brains and have one of your own biology teachers lead a professional development dissection activity that uses a sheep’s brain to begin to look at human neuroanatomy. Resources from the Dana Foundation, especially during Brain Awareness Week, have been particularly helpful, and we enjoy sharing this video when working with the St. Andrew’s faculty as well as educators around the world.

Deepening educators’ understanding of the relevant and well-researched neuroscience will surely have them thinking differently about teaching and learning. The space between my 9th grade biology class in 1983 and my reintroduction to neuroscience and neuroanatomy in 2007 along with my St. Andrew’s colleagues required me to relearn everything that I might have been taught as junior high school student. What if, when I entered that first class at St. George’s School in Spokane, I knew my content well but also had the current research-informed insights into how the student brain learns, works, and thrives? Imagine how much better my teaching and work with each student would have been.

That being said, we are still very early in figuring out how neuroscience can help teachers support the learning variability that exists in every classroom. But as we begin to rethink teacher preparation programs, and schools of education start to leverage how much we know about the learning brain into their curriculum, there is already an opportunity to start small. Teaching is a learning profession, and the adult brain and student brain is the organ of learning. This is just not “one more thing” teachers need to know. It is essential knowledge that I would argue is transformative. All teachers should want the material they teach to stick as long as possible, far beyond the summative assessment they have designed to measure the short-term retention of knowledge and skills.

I have been helping students memorize historical people, places, dates, interpretations, and events for more than 25 years. But not until I thought about memory alongside the evolution of neural networks and the myelination process was I willing to teach a little neuroanatomy side-by-side teaching about historical content, such as debates during the ratification of the United States Constitution.

Not only am I a better teacher today than I was when I first started my professional journey, but I also find myself even more fascinated with teaching and learning as I think about the only educational truth I know: every day, every student will bring his or her brain to my class.

Answer Key: (i) B; (ii) A; (iii) E; (iv) C; (v) D; (vi) G; (vii) F; (viii) H