By Glenn Whitman (@gwhitmancttl), Director, The CTTL

(Research Informed AP, Final Exam, and Project Preparation Strategies)

In 1997, I completed the Boston Marathon on a beautiful April day. I fondly remember passing through the Wellesley College gauntlet and cresting Heartbreak Hill knowing five miles were between me and the finish line. I had trained hard for the marathon, going on practice runs that varied in length of 5 to 20 miles. I had tried and found new strategies and mindsets to propel me through various parts of the 26.2 miles of a marathon course. All that preliminary work, and the focused training that comprised the final weeks leading up to the race, paid off. I achieved one of my life-long goals. A school year is very much like a marathon, and students are currently in the stretch drive. In front of them–their final five miles–are various types of summative assessments such as AP and final exams and projects, as well as various other national and state tests that vary by state and school type. Stress is high, memory is in demand, and students want to finish strong. The good news is that there are a number of research-informed strategies that students should consider and use depending on the subject and type of assessment. Using the right strategy at the right time is the key to being a successful student. Some have been tried out during the school year, but others are worth considering and reflecting upon. So, try some of these research-informed strategies and see which works for you. Remember that what is most important for your studying is to create the right amount of challenge as you practice. Just like practicing and training for a marathon, it should feel hard as you “bring to mind” the knowledge and skills teachers want you to demonstrate on upcoming assessments. Good luck! I. Spacing Effect

Decades of research have demonstrated that spacing out study sessions over a longer period improves long-term memory. In fact, the best time to review material is just when you start to forget it. In other words, if you have 12 hours to spend on a subject, it’s better to study it for three hours each week for four weeks than to cram all 12 hours into week four. The Learning Scientists have more to say on the Spacing Effect, so check out their podcast.

Try this:

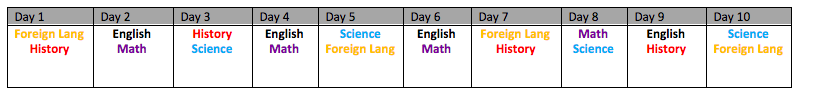

Use the Final Exam/Project schedule to plan for your exams and dedicated study time. Space your studying over multiple days (“study bursts”) and begin each new study session with a self-test. Here is one way to think about the spacing effect for each of your classes.

I. Spacing Effect

Decades of research have demonstrated that spacing out study sessions over a longer period improves long-term memory. In fact, the best time to review material is just when you start to forget it. In other words, if you have 12 hours to spend on a subject, it’s better to study it for three hours each week for four weeks than to cram all 12 hours into week four. The Learning Scientists have more to say on the Spacing Effect, so check out their podcast.

Try this:

Use the Final Exam/Project schedule to plan for your exams and dedicated study time. Space your studying over multiple days (“study bursts”) and begin each new study session with a self-test. Here is one way to think about the spacing effect for each of your classes.

II. Avoid Distractions and Switching Between Tasks (DO NOT MULTI-TASK!)

Research indicates that studying while multi-tasking, such as reviewing your notes while periodically checking social media or texting a friend, increases the time needed to study as well as drastically hurts the quality of your studying. You pay a “transaction” cost by switching between tasks. Despite what you might think, you do not pick up exactly where you left off. So, mono-task!

Try this: Disconnect. Find or establish a study location away from a computer, turn your cell phone off, and deeply dive into your studying and project design. Use your breaks as a reward to reconnect with friends and the world.

III. Study approaches (Passive vs. Active Studying):

II. Avoid Distractions and Switching Between Tasks (DO NOT MULTI-TASK!)

Research indicates that studying while multi-tasking, such as reviewing your notes while periodically checking social media or texting a friend, increases the time needed to study as well as drastically hurts the quality of your studying. You pay a “transaction” cost by switching between tasks. Despite what you might think, you do not pick up exactly where you left off. So, mono-task!

Try this: Disconnect. Find or establish a study location away from a computer, turn your cell phone off, and deeply dive into your studying and project design. Use your breaks as a reward to reconnect with friends and the world.

III. Study approaches (Passive vs. Active Studying):

Most students spend a large percentage of their time “passively studying.” Reviewing and re-reading notes in hope that information will be retained, produces relatively poor long-term memory retention. However, frequent “active retrieval” of information greatly enhances subsequent recall ability. The most important thing is to work at “bringing information to mind.” Even if doing so is really hard or impossible, the act of trying helps it stick in your long-term memory. See The Learning Scientists podcast titled “Bite-Size Research on Retrieval Practice Format.”

Try this (Pre-studying): Before you begin studying a defined topic, take a blank sheet of paper and list all that you can about the topic by “Actively Retrieving” information from your memory. This is called self-testing. You could also record your information-recall into your cell phone or other device and play it back to see what you remembered. Then check your notes to see how good your recall was. What did you know well? What gaps in your current knowledge still exist?

Most students spend a large percentage of their time “passively studying.” Reviewing and re-reading notes in hope that information will be retained, produces relatively poor long-term memory retention. However, frequent “active retrieval” of information greatly enhances subsequent recall ability. The most important thing is to work at “bringing information to mind.” Even if doing so is really hard or impossible, the act of trying helps it stick in your long-term memory. See The Learning Scientists podcast titled “Bite-Size Research on Retrieval Practice Format.”

Try this (Pre-studying): Before you begin studying a defined topic, take a blank sheet of paper and list all that you can about the topic by “Actively Retrieving” information from your memory. This is called self-testing. You could also record your information-recall into your cell phone or other device and play it back to see what you remembered. Then check your notes to see how good your recall was. What did you know well? What gaps in your current knowledge still exist?

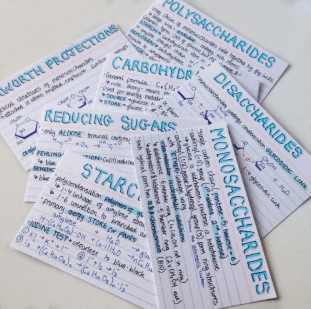

Try this (When Using Flashcards): Flashcards, whether hand written or via Quizlet, are an excellent, active study strategy when used correctly. Too often, students will turn them over too quickly, creating a false sense of understanding. Students should not turn over the card to check for an answer unless they have deliberately considered (struggled) for the answer. The not-knowing, struggle-pause, is the crucial step.

Try this (Post-studying): After studying a defined topic, close all your resources and on a blank sheet of paper self-test again by actively retrieving and recalling what you studied from your memory.

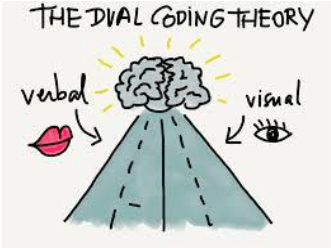

IV. Dual Coding (One of Mr. Whitman’s favorite strategies):

Try this (When Using Flashcards): Flashcards, whether hand written or via Quizlet, are an excellent, active study strategy when used correctly. Too often, students will turn them over too quickly, creating a false sense of understanding. Students should not turn over the card to check for an answer unless they have deliberately considered (struggled) for the answer. The not-knowing, struggle-pause, is the crucial step.

Try this (Post-studying): After studying a defined topic, close all your resources and on a blank sheet of paper self-test again by actively retrieving and recalling what you studied from your memory.

IV. Dual Coding (One of Mr. Whitman’s favorite strategies):

Recall information through the written word with the addition of pictures. As the Learning Scientists point out, “According to the original dual coding theory, the combination of words with visuals provides us with two different memory channels for later recall and retrieval.” Dual coding also helps move words from the abstract to the concrete by presenting them via pictures. Make sure you think hard about what relevant picture or image you select to represent words or ideas.

Try this: As you create flashcards, provide both a narrative and picture answer to the term, reading or idea. Also try taking a unit of study and create, by hand or virtually, an infographic of the material. Keep in mind that the quality of artwork is of NO importance. The act of creating the image, however low resolution, is what helps make it stick in your memory.

V. Reflection and “Test Corrections”

Recall information through the written word with the addition of pictures. As the Learning Scientists point out, “According to the original dual coding theory, the combination of words with visuals provides us with two different memory channels for later recall and retrieval.” Dual coding also helps move words from the abstract to the concrete by presenting them via pictures. Make sure you think hard about what relevant picture or image you select to represent words or ideas.

Try this: As you create flashcards, provide both a narrative and picture answer to the term, reading or idea. Also try taking a unit of study and create, by hand or virtually, an infographic of the material. Keep in mind that the quality of artwork is of NO importance. The act of creating the image, however low resolution, is what helps make it stick in your memory.

V. Reflection and “Test Corrections”

Reexamining work (tests, papers etc.) from earlier in the year is an excellent way to self-evaluate areas of strengths and weaknesses.

Try this: Research shows that attempting to correct wrong answers from previous tests is effective. Such “test corrections” should be first attempted without referring to any resources. Also evaluate the types of questions (such as multiple-choice and free response etc.) that have been more challenging and practice them more.

VI. Sleep (IS A STUDY STRATEGY!)

Reexamining work (tests, papers etc.) from earlier in the year is an excellent way to self-evaluate areas of strengths and weaknesses.

Try this: Research shows that attempting to correct wrong answers from previous tests is effective. Such “test corrections” should be first attempted without referring to any resources. Also evaluate the types of questions (such as multiple-choice and free response etc.) that have been more challenging and practice them more.

VI. Sleep (IS A STUDY STRATEGY!)

Research shows that sleep is for rest and learning as it aids in memory consolidation following studying. While you might be sleeping, your brain is actually working and consolidating all that you learned during the day.

Try this: Strive to get 8-hours of sleep a night (in a bed and not on your books). Avoid using technology 1-hour before sleep.

Research shows that sleep is for rest and learning as it aids in memory consolidation following studying. While you might be sleeping, your brain is actually working and consolidating all that you learned during the day.

Try this: Strive to get 8-hours of sleep a night (in a bed and not on your books). Avoid using technology 1-hour before sleep.

Additional Resources:

The Learning Scientists (Podcasts): http://www.learningscientists.org/

Retrieval Practice: https://www.retrievalpractice.org/

Retrieval Practice (Make It Stick): https://www.retrievalpractice.org/make-it-stick

Stop by the CTTL with any questions about these or other research-informed study strategies