Along with turkey and the onset of holiday music, tests and midterms are a feature of this time of year. Many schools have exams either before or right after the winter break, and others use a test to wrap things up before the long vacation. Does that sound familiar? So, how do we use MBE to help students thrive academically and balance this with well being? Specifically, what stress-reducing strategies for tests and exams can we employ?

In this article, we’ll answer:

- How we can help students get ready for tests by studying as efficiently and effect ively as possible

- Reducing stress can help students perform better on summative assessments. So what curricular adjustments can we make to reduce stress for students (and maybe ourselves, too)?

- What stress-reducing strategies we can share with students to help them manage their own stress

Helping Students Get Ready for Tests

- Spend some class time teaching students how to study efficiently and effectively alongside your content.

- Students like to reread notes and highlight text, or rewrite their notes multiple times. These are not effective strategies. They often feel nicer than other strategies, but that is because your brain is not working very hard.

- Instead, try spaced retrieval practice. For example:

- Give students a study guide. Have them take a topic and, on a blank sheet of paper, write out everything they know without their notes in front of them for three minutes. Then, they check their notes and fix any errors or missing information. Repeat with each topic on the study guide.

- Also try “teach it to learn it.” Students take each topic on a study guide and explain it to a friend, family member, dog, table, or into your phone. They check their notes to see if they missed anything or got anything wrong, and correct those explanations. Then move on to the next topic.

- Try practice questions. Post questions and answer keys online. Show worked examples, and, if possible, interleave worked examples and practice problems on the sheet. Grade these for effort, not correctness.

- Give students some time to study using these methods in class monitored by you.

- Give enough homework time dedicated to studying for students to be able to prepare for the test. One 30-minute homework the night before is not enough! Do not double-dip with other assignments; let studying be their sole focus.

- Spaced practice helps students recall. Because it is a bit rusty, recall takes more effort, which makes it stick better. So, they must start doing some retrieval practice in class and for homework at least a week in advance, and ideally two or more weeks out. Repeat this spaced out by a day or more in between.

- As part of the spaced retrieval practice assignments, have students submit evidence of how they are studying. For example, uploading a picture of their flashcards or efforts at recalling on a page.

- Talk to students about the danger of arts-and-crafts studying. For example, when making flashcards, the goal is to make them functional rather than beautiful so that they have enough time to study with them.

- Flashcards are a great way to study, but teach students how to use them correctly. They should be simple in style with not too much information on each. Read the front. If the students know the answer, try connecting it to something else. If not, they should take a moment to rack their brains before flipping. This pause to think is vital. If you dedicate 10 minutes to using flashcards in class, try pairing students up.

- Talk to students about neuroplasticity. Explain that studying using these methods might feel harder, but this is because they are rewiring their brains in ways that will help make the information stick.

Finally, remind students that only they can do the work. You can provide them with great study materials, great strategies, and the gift of time, but ultimately it comes down to them. Only they can do the work.

Stress-reduction Strategies via Curricular Adjustments

The summative assessments this time of year often bring stress. In moderation, for a short duration, and buffered by strong, positive relationships with adults, this can be okay. We know it’s part of the ebb and flow of the school year, and it will pass. For students, however, the last time they experienced this moment in full force was two years ago (at a level of academic challenge and with a student skill set that’s two grades lower). Stress may hit them a little harder or in different ways this year.

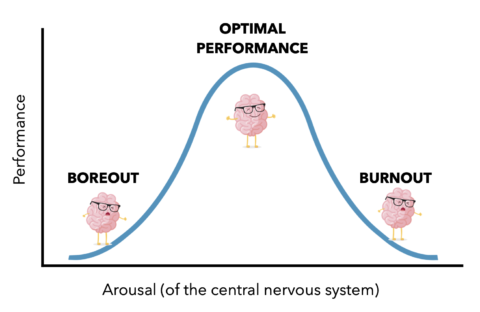

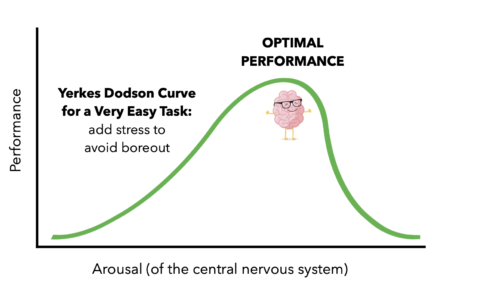

The Yerkes Dodson curve may already be familiar to you. Too much stress can lead to burnout, although too little may cause boreout. There is a sweet spot in between that we are always trying to keep our students in so they can perform at their best. This can be hard at this time of year – summative assessments bring stress.

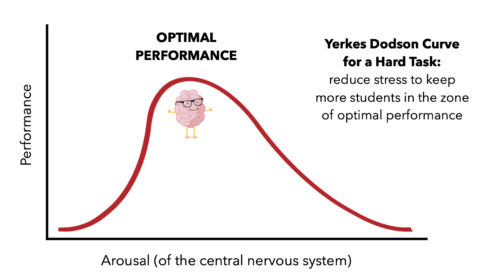

There is an additional nuance you might not be aware of, though. The more complex the task, the lower the level of central nervous system arousal that can be tolerated before performance deteriorates. This means that if a task is very hard, like an exam, we want to shift the curve to the left – helping students remain calm helps to keep them in the zone of optimal performance.

If we want our summative assessments to accurately show how students are doing compared to the learning goals of a course, we need to try to keep the stress level in the sweet spot. This means we need to actively manage the stressors within our control. By working together to reduce stress, we can help students perform their best on the complex tasks we are assigning them. Trying some of these simple things can help:

- Is there a topic I can cut from my plans so we can do the rest really well?

- If this test, paper, or project feels like a squeeze, does it have to happen in the first trimester/semester, or might it go better after the holiday break?

- Where can I use formative assessments to check if students are ready for the test?

- For a homework assignment of significant weight, can I give students time to get started at the end of class so they can ask clarifying questions?

- Does it make sense to provide an example end product (a B+ example may leave more room for discussion and creativity than an A+ example) ?

- Can I build a studying activity into class time, and – as part of this – teach students efficient and effective ways to study the material?

- Am I building enough studying time into homework, and not just expecting students to do it in addition to other assignments?

- Have I given students good study guides, example questions, and model answers?

- Can I improve directions or support materials, or simplify the production steps of a project, to reduce unnecessary executive functioning demands.

- Can I trim one part of a classic project I assign and still make it a good judge of what students currently know and can do?

- Can I turn a graded experience into an ungraded one in order to focus more energy on an upcoming summative assessment (e.g. a lab that would typically end with a lab report can become a lab for fun and exploration) ?

Strategies We Can Share with Students to Help Them Manage Their Stress

We must start by recognizing that behavioral changes in this category are hard to bring about. But, we think it is still worth trying to make a difference. Here are some strategies to share with your students:

Right before a test

- Know yourself. If last-minute review chatter hypes you up, great. If it stresses you out, plan to arrive early and listen to music on headphones, or claim your seat, step outside, and come back when the test starts and everyone is quiet.

- Free-write or free-draw for a minute to offload any concerns (about the test or otherwise). This reduces cognitive load and frees up mental bandwidth for the task at hand.

- Re-frame physical sensations of anxiety they may be feeling (elevated heart rate, sweaty palms, etc.) as a positive. They are signs of alertness and readiness to take on a challenge.

During a test

- Try this contraction exercise: while sitting up straight in a chair, press your palms together in front of you with your thumbs against your sternum. Press your feet into the floor. Take a breath, and contract every muscle in your body (legs, butt, abs, arms, shoulders) as hard as you can. Hold for 10-15 seconds and then release.

- Try box breathing.

At home

- Keep talking to students about the value of exercise (cardio releases endorphins! And resistance training stimulates Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) which is key for neuroplasticity), social connection, guided meditation, and sleep (we consolidate information into long term memory while we sleep – and sleep deprivation makes areas of our brain shut down).

- Take a look at this stress-busters guide for mode ideas.

Finally, remember that stress is cumulative, and everything else that is on that student’s plate – both in and out of school – factors in. People show stress differently, and some can mask it pretty well. And, everybody reacts to different stressors differently. If you ever have any stress-related worries about a student, make sure you notify the right people in your school according to your policies.

If you try any of these stress-reduction strategies and notice an impact, drop a quick note to tell us about it, or share on Twitter: @theCTTL

About the Authors

Dr. Ian Kelleher is a science teacher at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School, and Head of Research for its Center for Transformative Teaching & Learning. His work focuses on helping teachers translate the science of learning into everyday practices in their own classrooms, and measuring the impact. Ian is the co-author of “Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education,” and co-designer of Neuroteach Global. Ian is the inaugural Joseph and Kathleen Dreyfuss Faculty Chair for Research, an endowed position at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School for the lead CTTL researcher.

Eva Shultis is the Associate Director for Research & Product Development for the CTTL. Eva contributes to the research and development of Neuroteach Global, facilitates workshops for teachers and school leaders, and coordinates the annual Science of Teaching and School Leadership Academy. She also teaches and advises 12th graders at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School.