We feel lucky to be at a school that has prioritized the training of 100% of its preschool through Grade 12 teachers and school leaders in Mind, Brain, and Education (MBE) science since 2007. We have used MBE research to transform our daily schedule, refine how we teach and assess, re-examine how we teach literacy and reading, and, this past year, transition to distance and hybrid learning. Now, as we begin another complex school year, we are once again looking at insights from research in areas such as cognitive load, formative assessment, feedback, belonging, retrieval practice, and, perhaps most importantly, collective teacher efficacy, to best support all our learners’ academic, social, and emotional development.

The good news, if you are contemplating the start of your MBE journey, is that you are not alone. There are many other public, independent, charter, and international schools that The CTTL has worked with in its 10-year history. These schools have recognized how MBE can validate, inform, and transform many critical areas, such as the day-to-day work with each student, policies and routines, the nature of professional development, and strategic conversations about the future of teaching and learning in their schools and districts. As a result, more students are benefitting from teachers and school leaders who understand how the brain learns, works, changes, and thrives.

Our Own Introduction to MBE

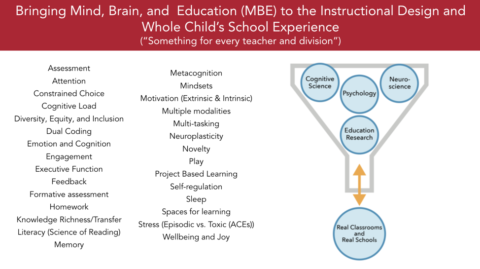

We were first introduced to MBE by Dr. Kurt Fischer and his team at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. Mind, Brain, and Education science is the transdisciplinary field that includes cognitive science, psychology, neuroscience, and education research.

At its conception, it was imagined that MBE would have a strong back-and-forth sharing of ideas with real schools (the orange arrows on the diagram below), though in practice this has proved challenging. Helping you and your school in this orange arrow zone is the mission of The CTTL. MBE offers many promising principles, but there is a crucial next step. We need to take these MBE-promising principles and translate them into everyday strategies, policies, and mindsets in our classrooms and schools. And only teachers can do this – this last vital “making it work in my context” step is beyond the practical knowledge of academic researchers. Only you can do this work.

MBE validates some practices that have long been part of the classic teaching canon, but also suggests we tweak other practices, stop doing some things we have held dear, and start doing some new things. The field of MBE offers something for everyone. And you don’t have to do everything all at once – MBE is a career-long journey.

When promising research and strategies in MBE are shared with educators, it is important to remember that the research likely was conducted in a highly controlled research study, and almost certainly in a school that was not your own. Therefore, we have always agreed with Dr. David Daniel that research can suggest promising principles that are worth trying in order to address needs, challenges and strategic opportunities in your school. But, and it is a big “but,” they need to be (1) translated to work in your particular context and unique voice as a teacher; and (2) evaluated for impact in your context with your students and revised based on what you find out. We will talk more about the second point in a future blog (spoiler: our plan is not as time or energy consuming as you think!).

Marshmallows? Please don’t talk to me about marshmallows.

As an example, I remember early in the CTTL’s MBE journey being shown the Marshmallow Study, and the results relating delayed gratification and a student’s future academic achievement. Many of us enjoyed watching the painful efforts of students trying to resist eating the marshmallow, but what we recall thinking is that the room in which the study was taking place looks nothing like a classroom. How can I translate such research to a real classroom? Is it even possible? Now that I know more about MBE, I realize the Marshmallow Study has little practical application for how I design my classes – but I also know a large number of MBE-promising principles that do, things I use every day and which are always a part of the conversation when I talk to teachers about teaching.

MBE for this complex school year

As we think about this complex school year, we are thinking hard about what MBE-promising principles to prioritize. What is readily translatable into a wide variety of teachers’ classrooms, and what is likely to have a significant impact? Every new school year, after a long summer break, we begin by focusing on two areas:

Formative/diagnostic assessment

Find out where students are by using a lot of no-stakes or “graded for effort” formative assessments (in the wise words of Dylan Wiliam, remember that any assignment can be used formatively), and adjusting our lesson plans based on what we find out. This year especially, do not make assumptions about what your students do and do not know – they may surprise you in either direction.

Build Relationships

Build connections and relationships, and make this a focus of the first six weeks of school. The time we invest in this is always returned, with interest, because of the class climate we help set. Strong, positive relationships underpin a great many MBE-promising principles, so deliberately work at this. It is more important than ever right now as students arrive back to what we hope is a more cohesive, in-school year after dramatically different summer and prior school-year experiences. Teachers and other trusted adults in schools play a front line role in helping each child feel like they can bring their full self to school each day, that their unique story matters in this place, that their teachers have high expectations of them and believe in their potential to reach them, that “my teacher gets me,” and that this is a place where they can face challenges and flourish. There is an awful lot that goes into making this happen. MBE offers us a lens and a toolkit that can really help.

What Else?

Beyond these two vital areas, what MBE-promising principles are teachers at St. Andrew’s focusing on this year? Here is a selection we think is important.

- Building a sense of belonging

- Managing cognitive load

- Using the science of literacy and reading

- Balancing stress

- Giving impactful feedback

- Designing a 60-minute class (the length of our Middle and Upper School classes)

- Teaching study strategies for efficient and effective memorizing

- Supporting executive functioning skills for all students

These areas, we feel, provide the chance for the biggest impact on the academic, social, and emotional development of all students. You may notice that, of course, they lie at the intersection of cognition, emotion, “rigor” and wellbeing – this is the year we are facing.

We also prioritize these areas differently by division, age group, and academic discipline. But, because we have built a common language and framework for MBE and used it to train all our teachers, we can more easily coordinate our approach across these groups. We also know that needs, priorities, and impact will change throughout the school year. Therefore, we have also built in time for our teachers to meet, discuss their MBE-informed successes, challenges, and current needs, and plan what to do next. We know from research that good professional development needs to be sustained, iterative, and focused on what students actually need. This year, more than any other year, we need to plan this into our schedule.

Conclusion

Schools and teachers around the world are at very different places in their year. Some schools in the US are a month into the year, and our friends in Sydney, Australia are only a few months away from their summer holiday. Whether you are at the beginning, middle, or end of the school year, we owe it to our students to use evidence to inform our daily work with them. Use MBE as a lens to help you find an area or two to tackle. Use MBE as a toolkit to find strategies that could help in these areas (our Research Base may help you here). Try something out, collect whatever easy-to-gather evidence and observations to see how it worked, and iterate from there. Find an MBE friend to share stories with and, occasionally, because it is the nature of our profession, to offload your “you won’t believe…” stories with.

And, please, let us know what MBE strategies you have chosen for your students and your school during another complex school year. We would love to share your stories with the growing international community of research-informed teachers and schools.

About Our Authors

Glenn Whitman is the co-author of “Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education” and directs the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School. Glenn is a former Martin Institute for Teaching Excellence Fellow and author of “Dialogue with the Past: Engaging Students and Meeting Standards through Oral History” as well as co-editor of Think Differently and Deeply, the international publication of the CTTL. Glenn earned his MALS from Dartmouth College and a BA from Dickinson College.

Dr. Ian Kelleher is a science teacher at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School, and Head of Research for its Center for Transformative Teaching & Learning. His work focuses on helping teachers translate the science of learning into everyday practices in their own classrooms, and measuring the impact. Ian is the co-author of “Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education,” and co-designer of Neuroteach Global. Ian is the the inaugural Joseph and Kathleen Dreyfuss Faculty Chair for Research, an endowed position at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School for the lead CTTL researcher.