By Dr. Ian Kelleher and Glenn Whitman

The feedback students receive from their teachers is always a critical part of their academic growth, but especially so in this complex school year. Each student receives feedback in many ways throughout the year, but this particular moment, when students and their parents or guardians receive their first trimester grades, is special. This is an important opportunity for positive and forward-looking conversations, and a chance to apply what we know from the science of learning to help each child think about their current performance and future strategies.

This year, in particular, it is even more important to focus on learning more than the grades, to focus on process over product. Attitudes, behaviors, mindsets, and character are not immediately visible in a grade, but are of immense importance. We cannot lose sight of the social and emotional challenges that distance and hybrid learning are having on students, and the added stresses that the pandemic has brought – all this has an impact. As we often share with students, a letter or numerical grade does not define who a student is or what their huge potential may be. This year, even more than usual, the grade alone tells a fraction of the story. However, too often the grade is where parent/student conversations about learning begin and end. So how do we use this “getting a grade” moment as a jumping-in point to learn about and help shape the larger story?

Ideally, the first trimester grades, this snapshot of current performance, will set up a dialogue between students and teachers, and between students and parents that focuses on: Where am I now? What do I need to do next?

Let’s explore some ways you can help do that…

1. Help your child see what is going well

Students are often not aware of what exactly it is they are doing that is helping them get the success that they are having. Obviously, the type of questions you might ask your child will vary depending on age, but these would be a good starting point for each class:

- What are your strengths in this class?

- What are you enjoying or excited about?

- What strategies seem to be working?

- What work are you most proud of so far this year?

- Ask if they see any common themes, and help them identify them. Children often have a harder time seeing these between-class patterns than we might imagine, so help them see it.

- Be careful with the language you use. Help your child connect their successes to the quality of effort they are putting in (I see you were using really good strategies and were working hard) rather than innate ability (I see you are really smart at math). Connecting successes to process – something a child has control over – rather than innate ability – which they do not – has been shown to help children persist in the face of struggle and develop a growth mindset.

- Give your child permission to work at strengthening their strengths as well as addressing current areas of challenge.

- Help them see purpose, relevance, and meaningful real-world connections to their classes when this comes up naturally. Doing so can boost motivation.

2. Help them identify areas of challenge

After exploring areas of success, shift the focus to areas of current challenge. The word current is important. Remind them that a school year is a marathon, not a sprint. Remind them that they have a great deal of neuroplasticity in their brains right now (much more than we adults do!), and that, by using good strategies and working with their teacher, they can help rewire their brains to make them better, more efficient learners.

Here are some examples of questions you might ask for each class:

- What is currently challenging you?

- What do you think your teacher would say about how you are doing in their class?

- How comfortable do you feel asking your teacher for help?

- What would you like your teacher to know about you that you are not sure they know yet?

- What are some strategies you have tried that just aren’t working? What are some strategies that others in your class are using? What are some strategies that are working in other classes that you could try here?

Again, the goal here is to link areas of challenge to strategy use, not to ability. Research suggests that being able to use the right strategy at the right time is the most vital factor in being a successful student. Help your child see that they are on a team with you and their teachers, and together, you are on this long mission to figure out what those strategies are.

Focus on strategies and self-advocacy

The fundamental shift we are trying to make is from a “I cannot do this” mindset, to a “I currently find this challenging – I need a better strategy” mindset. Your child’s teacher plays a critical role in helping them find and prune their toolbox of strategies. For this reason, self-advocacy is an important skill to develop during this grade review process. But it takes practice and sometimes courage. If students have questions about their grades and strategies for improvement, have them reach out to their teachers to schedule an appointment during office hours or at a time that is mutually convenient. Sending off that first email is a positive next step in strengthening the important teacher-student learning partnership. A longer term goal for your child is starting an ongoing conversation with their teacher about strategies.

Normalize struggle

Help your child appreciate that everyone’s brain is different, everyone has a different host of cognitive strengths and areas of challenge. And everyone struggles at times – struggle is a very normal part of school life – and because of all the people there who believe in you and support you, St. Andrew’s is a great place for that struggle to happen. Reemphasize that the school year is a marathon and not a sprint, and there is a lot of learning ahead.

3. Help your child plan next steps

Feedback is only useful if it leads to your child acting on it. So help your child come up with goals and an action plan.

- Taking notes, summarizing, and paraphrasing what they say, while you have a conversation on goals, can be more effective than having them make a list.

- Setting goals that are short term, specific, and moderately challenging tends to have a greater impact than establishing goals that are long term, general, and overly challenging.

- Having too many goals at once can freeze a student into inaction. So after compiling a list of goals, help your child prioritize them, and choose a sensible number to start working on (countable by the fingers on one hand of a cartoon character).

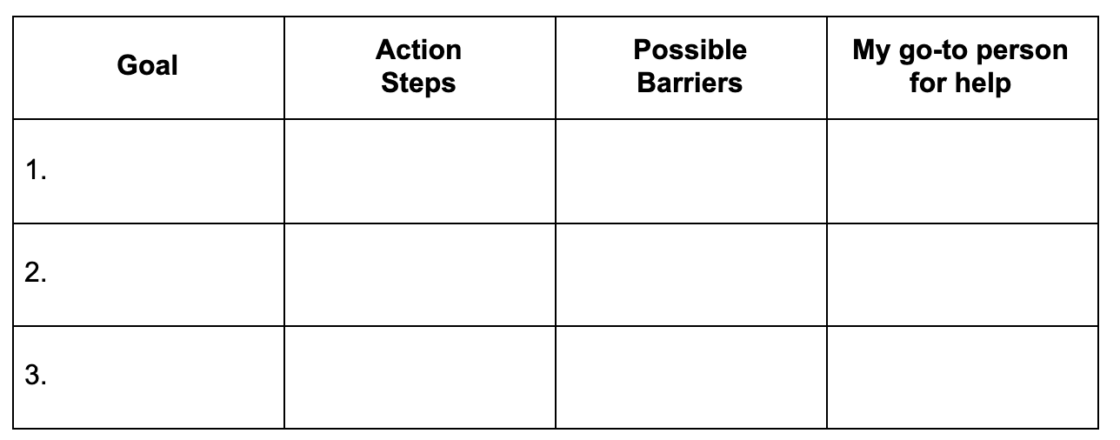

- Create an action plan. One way is with a table like this:

- Post the action plan somewhere visible in the house, and refer to it periodically, but not obsessively, to check on progress. Let the action plan evolve over time.

- If the action plan calls for your child to contact their teacher to set up an appointment, help them draft that email. There is often an emotional component to this that makes it harder than we might think, so support them in doing it.

Conclusion

In the CTTL’s work with students, we often like to share Professor Rob Coe’s quote that, “Learning happens when you think hard.” Receiving grades can be a thinking-hard moment. At St. Andrew’s, this happens through one-on-one conversations between teachers and students, and advisors and students. They lead to the evaluation of current learning strategies a student might be using and whether they are working for them. New research-informed strategies can then be suggested. The parent/student conversation complements this, and is equally important, especially in a year when parents have had the chance to observe their child’s learning more consistently than ever before.

Let us know how it goes.

Additional reading

- A free article on How to Help Students Focus on What They’re Learning, Not the Grade By Sarah Schroeder

- A research summary on “Metacognition and Self-Regulation” from the Education Endowment Foundation that has informed the CTTL’s work, including this summary poster

- A book we like: A Parent’s Guide to Powerful Teaching by friend of the CTTL, Patrice Bain.