By Dr. Ian Kelleher

There is no magic potion to help all students all the time, but there is something that comes pretty close. And it is utterly doable, even in distance learning times, and for the full range of learners. Indeed, it is great at filling in gaps in the schedule that might have appeared now that we have fewer places to go. It is often quite simple to do — yet actually, it turns out, very hard to get done.

A case for reading

Research suggests that reading can have a significant positive impact on learning. One reason for this is the ever-increasing knowledge gap that exists between those children that read and those that do not. Knowledge of words, ideas, places, people and things helps us understand more complex words, ideas, places, people and things. And this helps us understand more complex words, ideas, places, people and things. It is a snowball effect.

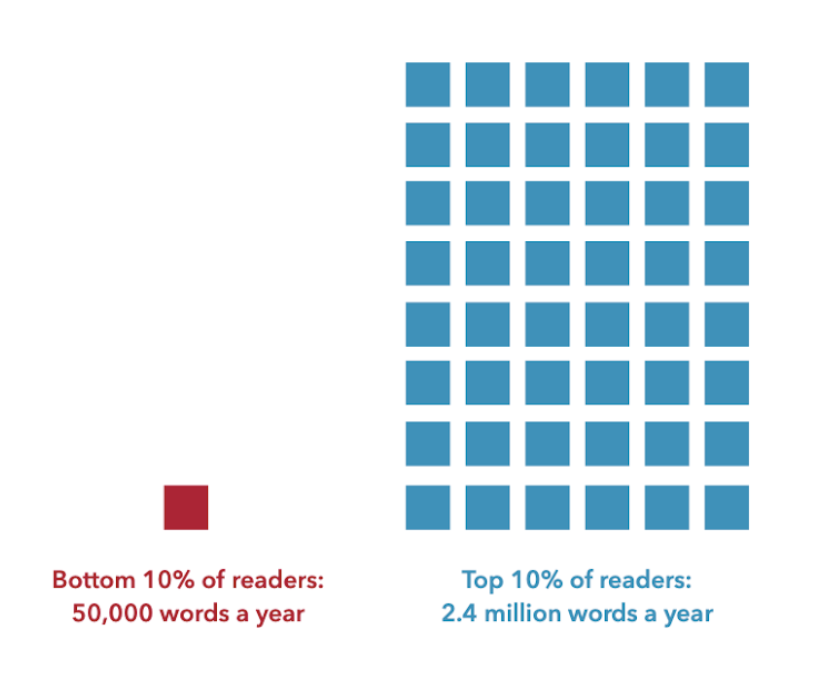

What’s more, the snowball effect is magnified because the difference between children who see themselves as readers and children who do not is huge. In this classic study, the bottom 10% of readers in fifth grade read 50,000 words a year, whereas the top 10% read 2.4 million words a year. This means the top 10% lapped the bottom 10% every week. Think about the accumulated difference in knowledge this makes — and how much easier or harder this makes learning. The study is getting old – it is from 1988 – but it is unlikely that things have improved since then.

What effect does the internet have?

Is non-stop exposure to the internet and social media rewiring our brains in ways that make it harder to read complex prose? UVA professor Dan Willingham suggests not:

A more plausible possibility is that we’re not less capable of reading complex prose, but less willing to put in the work. Our criterion for concluding “this is boring. This is not paying off” has been lowered because the Web makes it so easy to find something else to read, watch, or listen to… If I’m right, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that our brains are not being deep-fried by the Web; we can still read deeply and think carefully. The bad news is that we don’t want to.

Some strategies

But there is evidence to suggest that what you read matters. Books appear to be better than comics and magazines. So what can you do? Didn’t I say it is simple to do — but actually turns out to be very hard to get done? Here are some suggestions from Dan Willingham that work for students as well as you:

- Don’t assume that you have to have a long block of time to read. Bits and pieces add up (even chunks of five minutes).

- Be prepared. To make use of these times, keep books in places where you find yourself with a few minutes. Bathroom (Let’s not deny it). Kitchen… B. F. Skinner noted he read Thoreau’s “Walden,” which he kept in his glove box, in snippets when waiting for late-comers.

- The best preparation is on your phone. It’s not my favorite way to read, but you always have your phone with you. Get Kindle for your iPhone or Android.

- Don’t assume that you can only read one book at a time. If you’re reading multiple books, won’t you get mixed up? Probably not. But if you are really worried about that, start with books that have lots of short chapters or short stories.

- You don’t have to finish what you start. For a long time I assumed that if I started a book I was in some way obligated to finish it. Or maybe that if I didn’t, I had wasted my time in starting it. This attitude makes no sense. Don’t fail to start a book because you’re afraid it might turn out too challenging or emotionally hard, or whatever. If you don’t like the book, abandon it.

In addition, we suggest:

- Consider adding audiobooks into the mix. While they do not have quite the same effect as print books, they have most of the same effects, and they are far, far better than no books. For people with dyslexia, this is a great strategy for helping address potential knowledge gaps.

- Use an online app like epic!, which tracks, suggests, and provides access to a vast amount of books for children 12 and under.

- The St. Andrew’s library has many books that students can access electronically, as does your local public library.

- Read what you want, and don’t let anyone tell you that you shouldn’t be reading that. And if a book is not working out for you, teach yourself to just put it down.

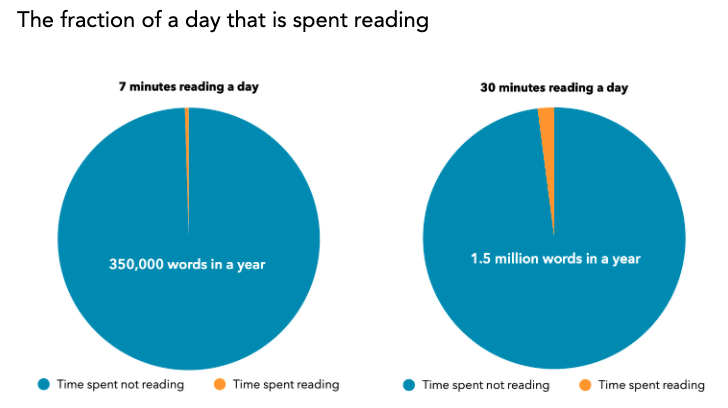

- Know that a small difference in reading routine can have a large difference in words read per year. Children 15 and under read on average just seven minutes a day. Look what a difference just 30 minutes a day makes — and it is not that much time to find (graphs are based on average reading speed in fifth grade).

Dr. Ian Kelleher is a science teacher at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School, and Head of Research for its Center for Transformative Teaching & Learning. His work focuses on helping teachers translate the science of learning into everyday practices in their own classrooms, and measuring the impact. Ian is the co-author of “Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education,” and co-designer of Neuroteach Global. Ian is the the inaugural Joseph and Kathleen Dreyfuss Faculty Chair for Research, an endowed position at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School for the lead CTTL researcher.